My Octopus Teacher

© Roger Horrocks

AGES AGO, I visited the invertebrate house of the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. to meet Hercules. Hercules was the zoo’s resident giant octopus, whose first impression I would later record as “a fleshy confusion of serpentine limbs and baggy head, a tentacled wreckage with a disturbingly human eye peeking out from within.” There was something about the way Hercules returned my stare. Something in that big, knowing eye of his—that feel of him inspecting me, the observer suddenly becoming the observed. It quickly went from me pondering some alien lifeform, to the two of us pondering each other like long-lost pilgrims meeting again after 600 million years wandering distant evolutionary galaxies. Hercules in all his unearthly appearance, evoked a certain unnerving familiarity.

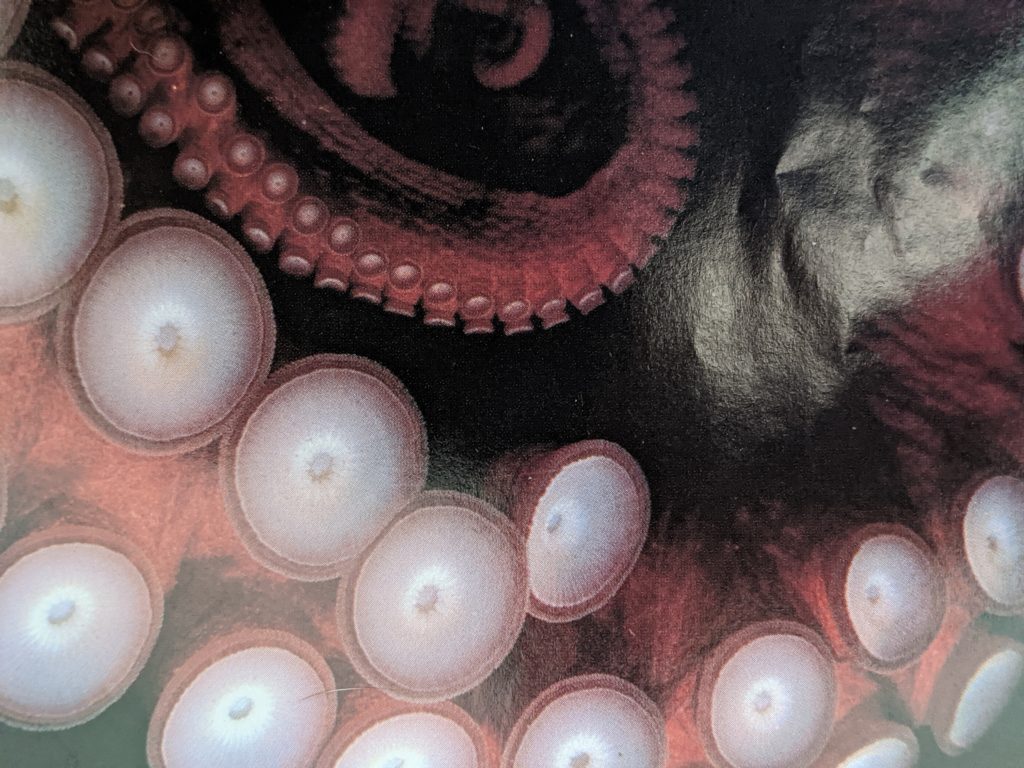

Which is to say that my meeting with Hercules was pretty much par for the course. Because octopuses do that to people. Divers, aquarium gawkers, scientists, scribes—all so commonly come away with similar readjustments of worldviews that have them waxing rapturously about the uncanny presence of this otherworldly creature. Never mind all the extraordinary feats of intelligence and magical shape-shifting displays of camouflage for which the octopus has become legendary. It is the one-on-one, eye-to-eye, that unhinges that human sense of higher standing. Because an octopus will examine you, size you up, and judge you. And depending on its assessment, he or she may shower you with curious affection, or mischievous disdain. An octopus may just as well reach out and caress you with one of its soft, sucker-studded arms, as squirt you with a jet of water from its siphon.

If you look closely enough, an octopus will draw you in, and charm or repulse you. And if you look really, really close—if you pour your entire being into seeing that octopus—you may even fall in love. I can’t vouch for having yet looked so closely as that. But I can say that I’m now standing in awe, having just watched and listened to the beautifully moving story of one who has.

Immersion

TEN YEARS AGO, a man and an octopus met in the sea off the West Cape of South Africa. The man, a forty-something filmmaker named Craig Foster—whose years of toil had left him burned out and sleepless, his health and family suffering, his “great purpose in life,” as he put it, “laying in pieces”—this man had come looking for salvation beneath the cold tempestuous waters where he’d grown up. The octopus—a member of the common species, Octopus vulgaris—was simply looking to hide. During one of Foster’s daily free dives in a frigid little kingdom of kelp forest, he came upon an odd edifice of empty shells rising so incongruously from a sandy patch of seafloor. In all his years in the water, he’d never seen such a thing. As he drew closer, the structure suddenly crumbled in a heap, and away swam its impromptu architect, an octopus.

Foster from that day vowed to follow that octopus. And over the following year, a love story happened, a story Foster so eloquently narrates in the new movie, My Octopus Teacher. It is a story entwining all the classic themes—love and fear, life and death, trust and betrayal, damnation and redemption. And by my own starstruck estimation, it is a movie with no less an ambition than to heal humanity’s dying relationship with this living planet we so precariously inhabit.

Our heroes’ story unfolds like this: Having met the octopus, Foster vows to be with her the next day, and every day after for a year. Every day he wades into the brooding seascape of jutting rocks and monstrous waves, into waters hovering around 46 degrees Fahrenheit, dressed in nothing but his shorts and swim fins, mask and snorkel. No scuba tank, no wetsuit—nothing separating Foster from the sea and the octopus but his own skin.

“Abandon hope all ye who enter here.” Craig Foster in South Africa’s Cape of Storms. © Roger Horrocks & Craig Foster

Down he dives. The cold takes his breath away. His body shivers. But he fights for those little windows of time when he can calm his rebelling mind and let the wonders of the kelp forest take hold—where suddenly, leaping off into this three-dimensional world, he is flying.

His body slowly adjusts, his lungs allow him longer stays between breaths. And thus he and the octopus start seeing a lot more of each other. At first she treats him with the proper suspicions of a soft-bodied morsel of prey facing a predator likely to eat her. She peeps out at him from the safety of her rock lair. When surprised out in the open, she wraps herself in a cloak of kelp, or morphs herself into a living rock that slyly creeps away as he watches. If all else fails, she simply clouds him in a puff of ink and jets away.

Contact

BUT AS SHE GROWS FAMILIAR with this persistent, goggle-eyed creature who just always seems to be there, her curiosity begins overtaking her fear. She starts inching out of her den, allowing Foster closer and closer before she scuttles back to cover. Until one day, Foster reaches out with his hand.

And in one of so many unforgettable moments of this factual fairy tale, the octopus replies in kind. She extends one of her eight, sucker-studded arms, and very delicately, intimately, begins smelling, tasting, caressing Foster’s finger.

First touch. © Roger Horrocks & Craig Foster

From there the friendship blossoms. The octopus begins incorporating Foster into her life, as he incorporates her into his. As he follows her in her daily rounds, she sometimes turns the tables, and starts following him. Until another turning point arrives, when she gives herself to him completely—when she, in a show of absolute trust, leaves the safety of her den behind, wraps herself around his hand, and rides away with him.

Through the following days and weeks we float along with Foster and the octopus, in their budding obsession with each other, swimming with each other, holding each other, learning from each other.

Lost and Found

THERE WILL COME moments of crisis in their relationship. Foster inadvertently startles her, sends her fleeing and gone for what he fears is forever. For days the crestfallen Foster inspects every nook and cranny in the kelp forest. He draws elaborate maps of every point of rock and sand and creature’s place in the forest’s web of life. He wills himself to think like an octopus, tracking her through the remains of her prey—an empty shell here, a crab leg there. And after an eternal week of searching, in yet another of those ethereal moments, there she suddenly is, waving from among the rocks to her long lost friend.

There will come moments of discovery and awe at the octopus’s mental and physical prowess, as a calculating, quick-witted hunter of prey and artful evader of predators. And as joyous instigator of child’s play, dancing and swiping among a school of fish she has no intentions of catching.

There will also come a shark, and a terrible attack that leaves a horrified Foster helpless as his friend is torn apart before his eyes. To tell you that she miraculously recovers does not begin to give away the story. Because of what eventually follows.

Letting Go

WHAT FOLLOWS IS THE MOMENT that has to be watched, when the octopus—after surviving the year in the perilous, predator-haunted environs of the kelp forest; after mating, and hatching her babies, and nearing the naturally ordained end of her mercurial life—begins to fade. She becomes listless, pale. Foster by now knows his octopus biology intimately. He knows how this story will end.

But you do not. And my words here would only mar the splendor of it. Only to say, that if by this point in the viewing you are not openly weeping, it would be wise to press a forefinger to your neck and feel for a pulse.

“I fell in love,” says Foster, still fighting tears to tell the tale long after his final poignant days with the octopus. “I fell in love with her, but also with that amazing wildness that she represented. What she taught me was to feel that you’re part of this place, not a visitor.”

Foster’s octopus teacher so beautifully, achingly unveils to him the universal soul that unites us all. In a world of people so rapidly losing touch with what’s left of the wild—a world where our youngest generation can name fewer wildlife species than Pokemon characters; where our most intimate touches with nature have been replaced by two thumbs tapping on the insatiable, parasitic screen affixed to our palms—in a world such as this, My Octopus Teacher offers a timeless lesson for all to embrace, with however many arms one may have.

Final embrace © Roger Horrocks & Craig Foster

XXX

Deeper Diggings

– Craig Foster has since gone on to co-found the Sea Change Project, a growing community of divers dedicated to protecting the Great African Sea Forest, into which he still dives every day.

– And of course, please do not miss seeing My Octopus Teacher

– The Soul of an Octopus, a book by the writer Sy Montgomery, is a wonderful accounting of her own love affair with octopus, and her probings into the mind, body, and soul of this endlessly astonishing creature.

– For those few who haven’t yet seen it, or need to see it again—because you really do— here’s the TED Talk by David Gallo, on the amazing camouflage of the octopus and its molluscan family of squids and cuttlefish. (Spoiler alert: the closing scene will absolutely blow you away.)

– As for my own contributions to the octopus admiration society, here’s a piece I wrote way back in the Pleistocene epoch of 1993, for a magazine then called Sea Frontiers:

The Familiar Stranger

BY WILLIAM STOLZENBURG

HERCULES IS A three-year-old, 45-pound Pacific giant octopus who resides at the National Zoo in Washington, DC. He alone in his modest tank is the star of the zoo’s invertebrate house, outdrawing even the vibrant colony of leaf-cutter ants, elaborately displayed in their plexiglas biosphere.

Hercules has himself. He clings quietly in his corner, a fleshy confusion of serpentine limbs and baggy head, a tentacled wreckage with a disturbingly human eye peeking out from within. Lacking props or fanfare, he flags the people down. Drawing near, his visitors’ perceptions rapidly begin to scatter. A woman grimaces, pronounces the beast ugly, and walks off. Her little boy lingers, transfixed, as if waiting for the creature to break into a smile and say hello. And so it goes. One eye sees a repugnant, cold-skinned alien, the other a fellow earthling in brilliant disguise. Both views, as it turns out, have good arguments.

All 100 or more species of octopus are, technically speaking, mollusks, as are oysters, clams, snails, and slugs. Soft bodies and hard shells unite the phylum Mollusca. But that is about as far as the octopus’s molluscan allegiance goes.

The octopuses, along with their brethren squids and cuttlefishes, have reduced the clunky shell to an internal calcified sliver and taken up life in the fast lane. They are jet-propelled predators and artful dodgers. And thinkers.

Their brain is huge for their body, and they are sharp students in the lab, running mazes, distinguishing shapes, learning as they go. Hercules has learned to open a jar of shrimp almost before his observers can activate their stopwatches. Octopuses in an Italian laboratory made the headlines last year when they showed they could learn tricks merely by watching a fellow octopus demonstrate. The octopuses are in a mental class of their own. But why they?

ACCORDING TO ANDREW PACKARD, a British zoologist who was among the first to expound on the question, today’s octopus is a sharply honed product of an ongoing battle through the ages with dangerous foes.

The octopuses’ ancestors were slow-moving, dim-witted, shell armored tanks, living defensively on the ancient seafloors. When bone- crushing fishes appeared, many of the mollusks retreated behind thicker shells and deeper water.

Contrarily, the archetypal octopus stuck its neck out. It cast aside its shelly armor and stood instead behind bare wit and anatomical daring. It invented an eye uncannily matching in form and function that of today’s vertebrate counterparts. It became the master of aquatic camouflage, with a nerve-triggered, kaleidoscopic talent for colors and patterns, instantaneously signaling moods, mesmerizing prey, or confusing predators.

The octopus is a survivor in our own style: bright-eyed, resourceful, and brash. It has become the chimpanzee of invertebrate behavior studies, the mischievous darling of aquarium keepers. But also, cautions octopus expert Martin J. Wells of Cambridge University, the octopus has become a trap for anthropomorphic admirers:

“It is very easy to identify with Octopus vulgaris because they respond in a very ‘human’ way. They watch you. They come to be fed, and they will run away with every appearance of fear if you are beastly to them. Individuals develop sometimes irritating habits, squirting water or climbing out of their tanks when you approach—and it is all too easy to come to treat the animal as a sort of aquatic dog or cat.

“Therein lies the danger,” says Wells. “The octopus is an alien.”

OCTOPUS SEX, for example, is not what humans might call a hot-blooded affair. Sans foreplay, the male octopus nonchalantly passes a packet of sperm through a groove in a special arm to the inner mantle of an obliging female. Its heartbeat scarcely varies. “It knows sex, but it does not get excited about it.” observes Wells. “Octopuses take these things calmly.”

The vertebrate world of intelligence is crowded with social creatures like dolphins, dogs, elephants, and humans. Yet the pinnacle of soft bodied intelligence is a loner. The octopus never knows its mother, makes no friends, and usually dies by the age of three. An Einsteinian mayfly.

The octopus tastes with its hands. It has three hearts. Its blood is blue.

SOBERING SPLASHES of octopus fact notwithstanding, something nevertheless draws us to them like family. It has been 630 million years since the common parents of octopuses and people divorced, but as both Packard and Wells point out, their subsequent paths have traversed hauntingly familiar territory.

As were our shrew-like forebears scuttling in the underbrush while Tyrannosaurus and its kind patrolled the landscape, so too was the early octopus raised in a terrifying world of vicious fishes and marine dragons. Octopus brains prevailed over brawn, something a soft-skinned ape can appreciate.

Animal behaviorist and unabashed octopus fan Jennifer Mather of the University of Lethbridge in Alberta is among the few who intimately know the octopus on its home turf. She has encountered in the sea’s tough urban environs of coral reefs and intertidal zones, a shrewd, eight-limbed animal with street savvy.

“The adaptability in the octopus is fascinating,” says Mather. “They have a very special memory. A memory of where they’ve been. The sit at home, go hunting, and come back. They crawl out in one direction crawl around, and come back usually from a different direction. Say you went to the market, and then to the liquor store, and then the drug store, and came right home without tracing your path. Octopuses do that quite readily.”

Octopuses also are quite adept at duping their enemies with the old shell game. They are continuously moving to new dens—not for want of richer hunting grounds, surmises Mather, but to keep their predators guessing. The appetizing octopus is no easy mark.

SOMETHING ELSE TO CONSIDER, between us and them: Much has been made of the bulky brain between the octopus’s eyes. Yet there is even twice as much neural firepower lying beyond, in its arms. Each of its 1,900 or so disk-shaped suckers is a supple, sensitized hand, able to smell, explore, wrench, and caress.

One of the decisive evolutionary leaps of the human being was the rising from all fours and the freeing of hands. Hands that could fashion a spear, sow seeds, pen a sonnet. The octopus has yet to reach for such heights. But its time may come. The octopus stands poised, bountifully armed for the occasion.

XXX

This information is worth everyone’s attention. How can I find out more?

I am really impressed together with your writing abilities and also with

the format for your weblog. Is this a paid topic or did you customize it yourself?

Eithedr way stay up the nice high quality writing, it is uncommon to peer a great blog like this

one nowadays..

my homepage – chillmo.digidip.net

Good post. I learn something totally new and

challenging on blogs I stumbleupon everyday.

It will always be useful to read through content from other authors and practice

something from other websites.