The Lonely Bull

THE CAPE BUFFALO is a wild bovine who lives upon the savannas and woodlands of east Africa. It’s a massive beast up to five and a half feet at the shoulder, with bulls weighing upwards of a ton. The oldest of these bulls wear the biggest horns, like Viking helmets, lending a warrior mien to their ill-tempered reputation. They are notoriously the testiest, most cantankerous members of their clan—a clan that is otherwise known for goring and stomping lions to death, not to mention any number of careless hunters who cross them. These old bulls are the ones who have helped cement the Cape buffalo’s standing as one of the five most dangerous animals of Africa.

There are any number of biological facts of the Cape buffalo that more truly and wondrously describe this creature. Yet it was this malevolent one, hyped as it may have been, that first flashed to mind one evening not long ago, when upon striding out of my tent in the Serengeti savanna, all but whistling a tune en route to cocktails across the way, I happened to turn and see standing thirty feet to my left the biggest, baddest, Cape buffalo bull on the planet.

Whoops.

Backpedaling to the porch of my tent, I watched as the patchy old bull ambled past and across the clearing. He headed straight for a thicket beside the mess tent, where he unceremoniously bedded down and disappeared in plain sight. Our camp crew later explained that he had recently taken up this nightly regimen as a means of seeking safety amid us humans, for fear of lions.

Where the Wild Things Are

IT’S BEEN TWO months since returning from safari on the northern plains of Tanzania: Tarangire, Ngorongoro Crater, Lake Manyara, Olduvai Gorge, Serengeti—iconic sanctuaries where the great herds and giant beasts of legend still roam amid the ghosts of humanity’s primordial past. It was the proverbial bucket-list adventure to where the wild things are. But after four days of touring this sacred land inside the armored bubble of a Land Cruiser—within a trunk’s length of elephants, within whispering distance of lions—for all the indelible memories, the one most deeply etched remains that pedestrian meeting with the doomed old buffalo.

How to explain? It certainly wasn’t for having witnessed any novelty of animal behavior. The old bull was practicing an established anti-predator maneuver called human shielding. He was using us to postpone a likely fate of his, which was to be torn to pieces by lions or hyenas out there in the bush. Such behavior is not uncommonly reported of old buffalo in the Serengeti camps. You can witness it as well in national parks of the American West, in certain gateway towns where the elk and deer and moose lounge in village squares and loiter on roadsides, where the wolves and cougars and bears fear to tread.

No, the novelty of that buffalo encounter was its intimacy. It was meeting the old bull on foot, minus the walls, minus the getaway vehicle. During our daily game drives we’d been dutifully instructed by our astute and affable guide Joseph to remain in the vehicle at all times unless chaperoned: No selfies beside the hyena kill, no petting the baby elephant, no climbing the kopje where lions are known to nap. And absolutely no straying from the tent after dark. All prudent advice. But….

But there would come a time, after the umpteenth stop for an elephant crossing, the umpteenth giraffe peering down through our open roof, the herd after herd of buffalo, zebra, wildebeest, and gazelle grazing roadside like so many livestock. There would come that urge to shuck the cage and walk free among the animals—to quit the Disney tour and explore the neighborhood up close and under foot.

Any number of Serengeti locals do so quite regularly. The Maasai people, whose pastoral lands border the park, are out there every day, on foot, children included, tending their goats and cattle and honeybees among the lions and leopards and buffalo, armed with nothing more than a herding stick. George Schaller, the American wildlife biologist who spent three years in the Serengeti in the 1960s conducting the now classic study of its lions, often ditched the jarring seat of his Land Rover to stroll free upon the plains:

“I was content to escape the insulation of the car. Feeling the rocks under my feet, seeing the vultures, soaring stiff-winged in the blue space, I was projected into the environment, alive, my humanity regained after confinement. It is all too easy to become alienated from nature, smothered by the effluvium of culture, the noises of motors, the secure walls of our homes, even the thoughts that dwell more on irrelevant abstractions than on the basics of living. To perceive this land, the plains and sky fused into a calm whole, forces man to relinquish his dominance.”

First Steps

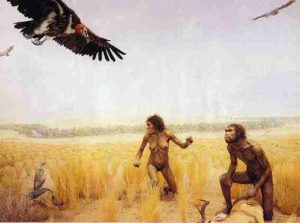

IT WAS THESE plains where our ape-men ancestors took their first steps toward becoming us. Down from the trees they came, walking upright, arms swinging free. As I wrote some time ago in a chapter about our African beginnings, these little proto-humans “had unimpressive fangs and nothing in the way of claws one could call weapons. Their leg speed was laughable. Yet by venturing into the open, they were venturing into competition with an accomplished cast of the fleetest and most fearsome carnivores on the planet.

“Out among a bristling menagerie of lions and hyenas, saber-toothed cats, wild dogs, and leopards, their forays might be construed as those of the fool or thrillseeker, some ancient progenitor of the modern rodeo clown. The walking apes were in fact pioneers of necessity. They had been pitched headlong into the Pleistocene’s turbulent era of shrinking woodlands and spreading grasslands, their sanctuaries of trees receding into isolated pockets. Like tadpoles in an evaporating puddle, they had either to grow legs or lay exposed to the mercy of the elements.”

The way we were

These savannas ruled by giant beasts were the crucible that forged the human animal, body and soul. There’s good reason why I or anyone might look upon them now with a certain longing, born of vague familiarity, of homesickness.

George Schaller too felt this longing. And with all due admirations, he heeded it. In 1968, as a curious aside to his lion study, he and an anthropologist colleague Gordon Lowther set out on foot to test how they, acting as two australopithecine hunter-scavengers, might have fared. I wrote of their adventure:

For one experimental stint of eight days, the two set up camp on the banks of the Mbalageti River, whose waters in the dry season drew the great herds of the Serengeti. Their front yard offered views of strolling elephants and curious lions observing them from the far bank. “A group of hominids could never have had it better,” wrote Schaller. “That night the lions visited us, roaring nearby and stumbling over the guy ropes as they circled the tent.”

Over the next week, the neophyte meat-seekers set off each dawn along the Mbalageti, steering clear of thickets and ravines where lions and Cape buffalo were most likely to lay hidden. They followed circling vultures to the leftovers of lions and disease, they watched cheetahs bringing down gazelles and plotted to steal their kills. They roamed as two red-blooded australopithecine scavengers in search of sustenance.

Schaller and Lowther settled into their primordial past, stalking with muscles taught, scanning the landscape for lurking danger and sizing up trees for emergency escape. They began to relish their daily adrenaline buzz, the air electrically charged with the hunt. In their heady thrillseeker’s euphoria, they grew careless. Seven times in the first two days, they found themselves beating hasty retreats after stumbling upon prides of dozing lions. “It is often said that one should never run from a lion,” Schaller recounted. “This is nonsense.”

That’s what was missing from the cushy seat of our Land Cruiser, that certain spice so briefly scented upon meeting the buffalo on foot. He came as a smelling salt to the senses, served with a side of humility. He left that haunting pang of sympathy and sorrow for his plight, as reminder of the kindness embedded in our otherwise checkered humanity. Most problematically for me though, he added one more to-do on that already overbooked bucket list, to return and retrace our Serengeti tire tracks with those of my feet.

For the meantime, I’ll do with imagining that old buffalo as still ambling about, and gifting some other lucky tourist with a little kick in the safari shorts—as reminder to take foot, give thanks, and nurture those better apes of our nature.

XXX

Resources:

Good Earth Tours – Our tour company took great care of us, through some rather challenging times. And our safari guide Joseph knew everything there was to know. And yes, they do offer walking safaris!

Golden Shadows, Flying Hooves, by George B. Schaller. One really good read, on the lives of the Serengeti lions and how it feels to live among them, by one of the greatest of wildlife biologists.

The Battle at Kruger. For a look at how Cape buffalo sometimes deal with lions, join the 88 million others who have viewed this amateur video.

A couple of many academic papers on the tenuous future of the Serengeti:

Kideghesho, Jafari R. 2010. ‘Serengeti shall not die’: transforming an ambition into a reality. Tropical Conservation Science 3 (3):228-248.

Kideghesho, Jafari R., Houssein S. Kimaro , Gabriel Mayengo, and Alex W. Kisingo. 2021. Will Tanzania’s wildlife sector survive the COVID-19 pandemic? Tropical Conservation Science 14: 1–18.

Organizations helping to keep Africa wild:

Isoitok Camp Manyara (Glamping made to somewhat resemble a Maasai village, we stayed here our last night on the mainland and were thoroughly enchanted.)

Another poignant narrative, Will… Thank you for giving us a glimpse into your recent Tanzania trek… Thanks for sharing the images from Chris and Lori, as well… Now adding to my bucket list…

As always, thanks Stacy. Sounds like you’re ready to take the walking tour!

Very much looking forward to seeing the next chapters to spring from your magic quill Will!

Spring? More like lurch!

I knew Lurch. Lurch was a friend of mine. Bard Stolzenburg, you’re no Lurch. (With apologia to the late, great Sen. Lloyd Bentsen, (D-TX)

And another thing. That ape-woman creature is really sexy. You naughty boy!

graphics were selected with St. George in mind. Speaking of Lurch (with apologia to the late, great Ted Cassidy), did you know he was actually 6’9″?

Not a great reader but every time I read your blogs I cannot put it down. I have learned more about the African buffalo in your writings than I knew my entire life. All I can say is thank you so much.

Thanks Mr. Mike. Learned a few things myself. That buffalo’s a pretty good teacher!